Sixth Amendment Right To Counsel And Recorded Phone Calls

People v. Johnson

2016 NY Slip Op 02552

New York Court of Appeals

Decided on April 5th, 2015

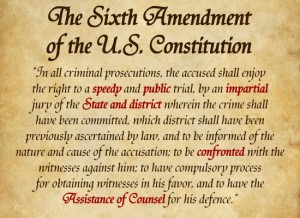

Issue: Whether a Defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel was violated when the New York Citys Department of Correction (the Department) released recorded telephone conversations to the District Attorneys office that the People used against him at his criminal trial.

Holding: The Court of Appeals held that there was no violation of defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel when his recorded phone calls were used against him at trial. ?The Sixth Amendment right to counsel prohibits the use of incriminating statements deliberately elicited from a defendant by government agents (Fallers v United states, 540 US 519, 524 [2004]; United States v Henry, 447 US 264, 270 [1980]). The right to counsel protects persons, whether in custody or not against the use of incriminating statements made as the result of governmental interrogation, including prosecutorial inducements to make such statements without the assistance of counsel (People v Velasquez, 68 NY2d 533, 536 [1986].

Moreover, the right to counsel protects an accused in pretrial dealings with the overwhelming, coercive power of the State, by excluding incriminating evidence obtained by agents of the State in violation of that right. Concomitantly, the exclusion of incriminating evidence obtained by agents of the State operates to deter their inferences with the rights of the accused. A violation of the right to counsel requires the involvement of the State in eliciting that evidence.

Under the Rules and Regulations of New York, inmates are permitted to make calls during their incarceration, subject to the Departments authority to listen to and monitor all calls not otherwise exempted or privileged.

Facts: Defendant was arrested on charges of robbery, and when he could not make bail he was remanded to Rikers Island. The People acquired from the Department dozens of recordings of telephone conversations that defendant placed to his friends and family. Defendant argued that (1) the disclosure was unauthorized and unwarranted under the Departments Operation Order, and (2) that disclosure to the prosecutor undermined defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel. The Court denied the motion.

At trial, the prosecutor introduced evidence and played the summation excerpts from defendants recorded telephone calls. In these calls, defendant made incriminating statements and used offensive and vulgar language to discuss the victim and other individuals involved in the robbery. The jury convicted defendant and the Appellate Division rejected defendant’s challenge to the admission of the recordings, finding that the calls were admissible, notwithstanding that defendants right to counsel had attached. A judge of the Court of Appeals granted defendant leave to appeal where they held that the defendant acknowledged that any such defective notice could be ameliorated by an express Department notification that the recorded calls may be turned over to the District attorney. Accordingly the order of the Appellate Division is affirmed.

…defendant made the telephone calls aware that he was being recorded, and the mere act of recording is no different from an informer sitting mute, not provoking or prompting conversation but merely listening to a statement freely made. Under these circumstances, where the government’s role is limited to the passive receipt of information, the informer is not, as a matter of law, an agent of the government…

Legal Analysis: The Court of Appeals held that inmate telephone conversations are subject to electronic recording and/or monitoring in accordance with the Departmental policy. An inmate’s use of institutional telephones constitutes consent to this recording and/or monitoring. As a general matter, the Department has identified the types of calls that trigger monitoring as those involving institutional and public safety and security. New York Citys District Attorneys Offices may request a copy of an inmate’s recorded call. Such requests are decided within three business days by the Departments Deputy Commissioner for Legal Matters, although the Operations Order does not explain the criteria for granting or denying such requests. Upon approval of a request, the copy of the recordings is turned over to the District Attorneys representative, who signs a form indicating receipt.

The Court held that in order to properly address defendant’s claims, they clarified what defendant did not allege on this appeal. He did not allege that any conversations with his defense counsel were recorded and admitted at trial, or that the Department permits such monitoring. Defendant recognizes that the Operations Order expressly prohibits the recording and monitoring of conversations with an inmate’s attorney. Nor does defendant assert that the intention of the Citys regulation or the Departments Operations Order is to create and collect information strictly for use by the prosecution against a detainee at trial. Defendant candidly admits that the Department has a legitimate interest in recording and monitoring detainee telephone communications. Defendant claims the practice violated his right to counsel, exceeds the scope of the Departments authority, and was conducted without defendant’s consent. The claims are either without merit or unpreserved and therefore do not warrant reversal and a new trial.

The Court held that in order to properly address defendant’s claims, they clarified what defendant did not allege on this appeal. He did not allege that any conversations with his defense counsel were recorded and admitted at trial, or that the Department permits such monitoring. Defendant recognizes that the Operations Order expressly prohibits the recording and monitoring of conversations with an inmate’s attorney. Nor does defendant assert that the intention of the Citys regulation or the Departments Operations Order is to create and collect information strictly for use by the prosecution against a detainee at trial. Defendant candidly admits that the Department has a legitimate interest in recording and monitoring detainee telephone communications. Defendant claims the practice violated his right to counsel, exceeds the scope of the Departments authority, and was conducted without defendant’s consent. The claims are either without merit or unpreserved and therefore do not warrant reversal and a new trial.

Here, Defendant alleges that he did not consent to the Departments dissemination of his recorded conversations simply by using the Rikers Island telephones. According to defendant, his consent cannot be implied because he was never informed that the recordings may be released to the prosecutor. Defendant acknowledges, though, that any such defective notice could be ameliorated by an express Department notification that the recorded calls may be turned over to the District Attorney.

Defendant claims the People; by combing through all the telephone calls are able to obtain information about a defendants defense strategy and decision-making, outside the presence of counsel, in violation of his Sixth Amendment right to counsel. He claims that the Department acts as an agent for the District Attorney in eliciting potentially damaging statements merely by recording the calls. However, he points to no individual that the District Attorneys Office, or for that matter the Department, employed as an agent of the government who acted in a manner to prompt or provoke information from defendant. The Court of Appeals held that they therefore find no support in the law or facts of this case for defendants constitutional claim.

The Department did not serve as an agent of the State when it recorded the calls it turned over to the District Attorneys Office. Defendant was not introduced by any promise, or coerced by the Department, to call friends and family and make statements detrimental to his defense. Nothing in the record suggests that the Department solicited, elicited, encouraged or provoked these conversations. Moreover, defendant made the telephone calls aware that he was being recorded, and the mere act of recording is no different from an informer sitting mute, not provoking or prompting conversation but merely listening to a statement freely made. Under these circumstances, where the government’s role is limited to the passive receipt of information, the informer is not, as a matter of law, an agent of the government, People v Cardona, 41 NY2d 333,335 [1977].

Defendant asserts that the particular circumstances of detention support treating the Department as an agent because detainees have limited access to outsiders, including their lawyers. Thus, left without options available to those able to make bail, a detainee, out of necessity, makes statements during telephone conversations that are detrimental to the defense. However accurate this description may be of the realities of the Rikers Island pretrial detention environment, and the opportunity presented to prosecutors by the conditions under which detainees are confined, it does not establish the Department acted as an agent in defendants case. Accordingly, the order of the Appellate Division should be affirmed.